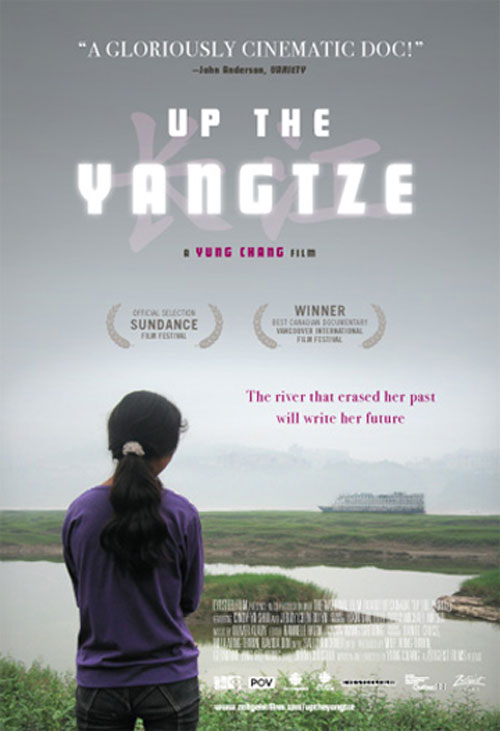

Nothing suits a sociocultural documentary portrait of a nation more powerfully than the gestalt of sweeping, irreversible change reshaping and redefining the landscape to an immeasurable degree, while the cameras are rolling. Yung Chang’s Canadian-produced documentary Up the Yangtze benefits from just such an element. An essay on geopolitical transition that could not possibly have been made at a riper or more advantageous moment in history, it also embodies an autumnal film of death and rebirth — death to innumerable generations of indigenous Chinese culture, rebirth to a country now shaping itself and emerging as an anglicized economic superpower on the world stage. And that dual reality carries overtones not bittersweet, but in Chang’s hands, deeply and profoundly sad. Even as this masterfully conceived and executed film illuminates the mind’s eye, it succeeds in breaking one’s heart.

As complex and multifaceted as 21st century China is, it could easily demand a 12- or 14-hour documentary miniseries. Chang never once shies away from the complexity of his subject, which makes the breadth and profundity of the picture’s insights within its intimate scope that much more remarkable. The director posits the film against the backdrop of the massive Three Gorges Dam installation — an overpowering symbol of the country’s industrialization. The largest hydroelectric project in the world (as the narrator reminds us), it will do much to revitalize and reshape China’s economy, but it also means raising the mythical Yangtze River to unseen levels and literally drowning out the villages of uneducated, illiterate peasant villagers who ostensibly have nowhere else to go — thus obliterating centuries of Chinese history.

Chang’s approach involves humanizing this bifurcated tragedy by filtering it through the lives of two subjects: 16-year-old Yu Shui, the sweet-natured (if taciturn) daughter of a gaunt peasant farmer on the Yangtze banks whose family suffers from abject poverty, and (in an unrelated thread) 19-year-old aspiring vocalist Chen Bo Yu, who hails from an affluent family. He’s as much a victim of China’s government-sanctioned one-child-only policy as he is of his own gross conceitedness and pomposity. As Yu Shui heeds her mother’s request to skip secondary school and serve as a hostess on a luxury cruise line, sailing up and down the Yangtze and catering to American tourists (a job that will generate extra income for the clan), so Chen Bo Yu also takes a job as a host on the said ships.

Chang’s heart and soul lie with the peasant villagers, and nothing in the film carries as much lyrical beauty or cultural authenticity as intimate, candidly shot scenes of Yu Shui’s family huddled around dinner in their jerry-built shack on the Yangtze banks. To the credit of both the director and his subjects, one instinctively develops feelings of emotional attachment to this clan and empathy with their plight becomes an automatic. Chang turns to Yu Shui’s family as representatives of “the old China,” and indeed, in the wizened face of her middle-aged father one can see the product of generations upon generations of Chinese residents, stretching back into the dynastic era. As a measure of Chang’s success, one feels an overwhelming, palpable sense of sadness at the thought of not only their home (and, thus, vital elements of indigenous Chinese culture) being indiscriminately wiped out by the sweeping tide of industrialization, but thousands upon thousands of similar residences and family units also extinguished.

The events that unfurl on the cruise ship form a striking juxtaposition alongside the said familial scenes, and contrastingly lend an aura of deliberate, almost sly cynicism to the proceedings. The proprietors of the line promptly anglicize their new recruits by giving them new names (“Jerry” and “Cindy”), teaching them English, and schooling them in warming up to their American patrons. Against this backdrop, we witness the dark underbelly of capitalism — greed — rearing its ugly head. That theme waxes particularly potent when Chen Bo Yu delves headfirst into the Western affluence of the ship and its patrons, and his (already intolerable) cockiness shoots through the roof; he delivers a couple of ghastly, profane, and egocentric asides to the camera on the ubiquity of American tourists and how it only makes good financial sense to fraternize with wealthy middle-aged visitors because both younger Westerners and elderly Americans tip so poorly. (He also congratulates himself and expresses pride over his reception of 30 American dollars.) Nor does Yu Shui (sweetness aside) emerge as particularly immune to these lures; despite her said goal of regularly shuttling monies back to her family, we never once witness her doing so, and she seems more willing to fritter away her earned monies on high-end apparel and accessories such as flashy earrings than she is to support her folks.

The fiscal logic behind China’s shift away from rurality and toward an urban, westernized market is readily apparent and easily grasped, and may seem like an obvious move for the country in the 21st century global economy. But Chang seems to be asking throughout the film, “What of the cost? At what price glory?” And what of the government officials who — we learn — have literally strong-armed peasants into relocation, often demanding bribes for more upscale residences and reducing one shopkeeper to tears on camera? The wisdom of the film lies in its realization that there may not be any easy answers, and that coming face to face with an understanding of the concomitant losses represents a significant step forward.