Today, many regard Jack Kerouac as a revolutionary — one who liberated more conventional literary forms with a freewheeling, stream-of-consciousness authorial style that fluidly bridged poetry and prose. A trademark joy lies at the heart of Kerouac’s magnum opus On the Road and its successors, such as Big Sur and The Dharma Bums, that enabled him to capture the restless spirit of the postwar generation at its peak. Yet this only represents one side of the equation: If one steps outside of Kerouac’s catalogue and reads more objective material about him — such as Ann Charters’s dispassionate 1994 tome Kerouac: A Biography — it becomes apparent that self-myth and mythmaking were central to Kerouac’s life and art, and that a broad chasm opened up between the writer in his private life and the thinly veiled fictionalizations of himself and his friends on the page, such as Sal Paradise (Kerouac), Dean Moriarty (Neal Cassady), and Carlo Marx (Allen Ginsberg). Stripped of myth, the real Kerouac and his friends lived lives of desperation — directionless, strung out on alcohol and barbiturates, riddled with despair; in fact, Cassady and Kerouac each died before the age of 50, Kerouac from the cirrhosis brought on by years of unmoderated drinking.

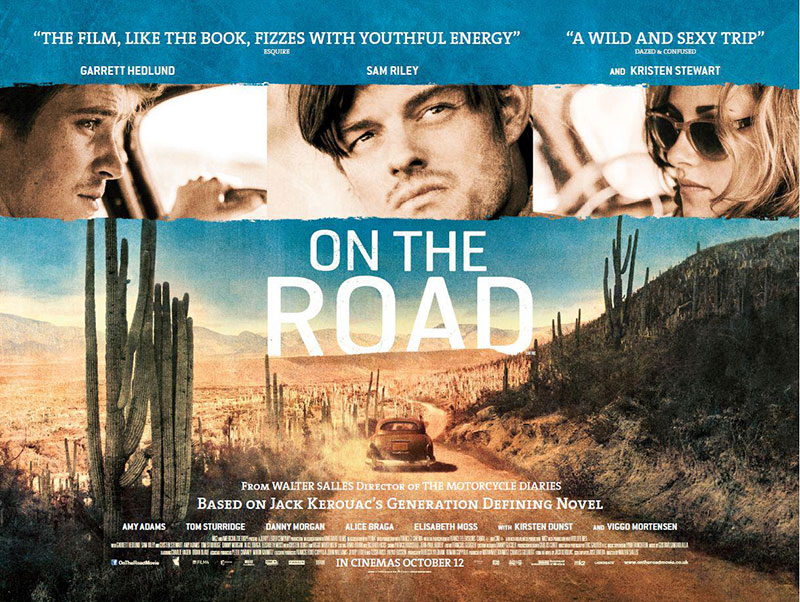

The oddest aspect of the movie version of On the Road is the fact that — despite preserving events and figures from the novel itself — it keeps its feet firmly planted in the lives of the actual Beat writers in lieu of Kerouac’s inflated characterizations. Not only does it not lasso the youthful exuberance of Sal and Dean’s traveling, it travels to the opposite extreme: Director Walter Salles Jr. and screenwriter José Rivera paint the whole Beat Generation as a downbeat, dead-end group of irresponsible young men, whose attempts at rebellion only succeeded in breaking a lot of hearts — such as that of Carolyn Cassady aka “Camille” (here beautifully played by Kirsten Dunst), Neal’s emotionally tortured wife, whom he cruelly abandons at one point with two infant children. Salles and Rivera also make a point to depict visually (though it is never stated outright) the physical, emotional, and mental strain that drugs took on these wistful rebels.

As a result, the picture doesn’t even begin to work as an adaptation per se, and does nothing to disprove the commonly held misperception that On the Road is an unfilmable book. It neither sides with Kerouac’s generation’s countercultural values, nor does it find an equivalent for the jazz-like ebb and flow of Kerouac’s language. Salles is a competent, gifted director, but he’s too square for this material; it demands a filmmaker willing to push the envelope stylistically with his camera, with a cinematographic technique comparable to what Kerouac did on the page. Ideally, a treatment of the Beat Generation would go even one step further by juxtaposing Kerouac’s “real” life with his “literary” life to explore the critical role that mythmaking played in his development as an artist. But that doesn’t happen here.

One can approach the picture as a straightforward biopic of Kerouac and Cassady (not unlike John Byrum’s 1980 Heart Beat), and it generally works on that level. Nothing in it is inept or klutzy — created under the imprimaturs of heavyweights Salles, Rivera, Francis Ford Coppola, and Marin Karmitz, it reflects professionalism on all levels. And the performances are uniformly extraordinary: In addition to Dunst, leads Garrett Hedlund (as Dean/Neal) and Sam Riley (as Sal/Jack) perfectly evoke the authors they are depicting, and the picture features a wealth of small, eloquently realized turns — an emotionally persuasive Kristen Stewart as a lover shared by both men, Tom Sturridge as a bonked-out (and man-hungry) Allen Ginsberg, and Viggo Mortensen and Amy Adams in magnificent portrayals of William S. Burroughs and a grungy Joan Vollmer (two evocations so brilliant and on-target that you wish Salles and co. would drop Kerouac and just focus on them). The ensemble’s performances are the movie’s pride and joy and make it worth seeing (if not essential viewing); the only problem with reading it as an objective depiction of Kerouac’s life is that we never, even for a second, get a sense of the scope or breadth of his talent from what’s onscreen. The film may be adequate and moderately enjoyable, but overall, it falls short of its full potential.