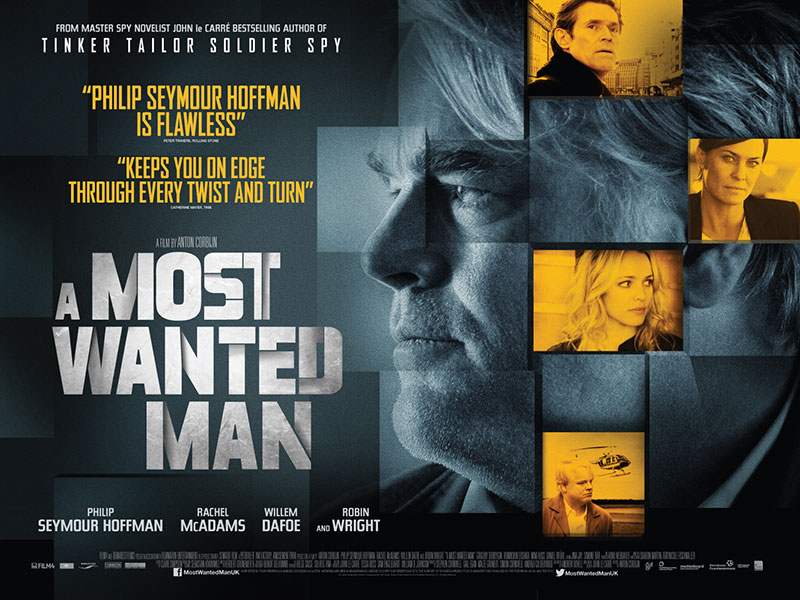

Günther Bachmann (Philip Seymour Hoffman), the main character of Anton Corbijn’s John Le Carré adaptation A Most Wanted Man, is a post-9/11 operative in a sub-rosa Hamburg counterterrorism organization. His agency functions as a kind of loose cannon — it flies beneath the public and media radars, and operates independently of the GSG-9, the formal German governmental unit assigned to combat extremists. As the story opens, a battered Muslim vagrant from Chechnya named Issa Karpov (Grigoriy Dobrygin) drifts into town, and his ominous behavior and appearance magnetize the attention of Bachmann’s unit and the GSG-9. The agencies harbor a shared concern that Karpov might be a possible jihadist threat, especially given what they discover of Karpov’s late father’s criminal past, but Bachmann and his acolytes disagree with the GSG-9 suits over how quickly to act — Bachmann expresses recalcitrance to arrest Karpov until the outline of the scenario gains focus, an equivocation that intensifies as the days pass. In a short time, Karpov earns the friendship and trust of a beautiful young social worker named Annabel (Rachel McAdams) who tries to refute the suspicions surrounding the illegal immigrant and fights for his welfare — especially after she learns that he was tortured in Russia and that he’s deferring on collecting a huge inheritance from his dad’s bank account. Meanwhile, Bachmann concocts an ingenious plot to use Karpov to fight a potential source of terrorism that will also — if all goes according to plan — result in the young man obtaining amnesty. The GSG-9, however, would prefer to ignore Bachmann’s strategies and snatch Karpov up to be doubly certain of eliminating all risk.

This might sound wildly complicated. To the credit of Corbijn and scribe Andrew Bovell, the jigsaw-puzzle-like premise remains lucid and transparent enough that we never for a second feel lost or confused. Curiously, though, the details of the spy plot are far less significant in retrospect than Bachmann’s own human story. A haunting question lingers beneath the surface of the action: We keep asking ourselves how and why Günther — despite his cool amiability, his evident control and dexterity at handling spy investigations, et cetera — also seems so emotionally rigid, so locked inside of himself, so unwilling to trust even his closest and dearest colleagues, so isolated and guarded with his personal life. We eventually find out exactly why — boy, do we ever.

Per Le Carré’s standard MO, Bachmann and all of the men and women in his unit are severely damaged in more ways than one, with traces of moral bankruptcy and a propensity for ethical compromise existing alongside a basic core of integrity. Bachmann delivers the film’s message in one critical scene: All men, even those considered morally just and upright (including Bachmann himself), have some impurity, some evil, in them. It’s a dark perspective — cynicism handed to us on a platter — but one all too familiar from Le Carré’s fiction. Think, for example, of George Smiley in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy or Alec Leamas in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. We’ve seen variations on this character before — basically good but internally damaged — and we can easily recognize him this time. And per the actions of those prior Le Carré antiheroes, we come to realize that Günther’s job rests on a bedrock of deception and manipulation. For instance: In one piquant, unsettling scene, eroticism comes to the fore, as Günther embraces a young male informant — a gesture which continues for such a protracted time that it eventually leaves the realm of the paternal and begins to assume homosexual overtones, followed by a verbal hint of the man’s arousal. But complicating the situation is the young man’s threat (just prior to that hug) to abandon his professional obligations to Günther — which casts suspicion on the legitimacy and sincerity of the romantic embrace. Is Bachmann gay? Perhaps not; perhaps Bachmann knows that the young man is gay and just wants to tease him to keep him on a leash. Pretense pervades within the spy realm, and virtually nothing that espionage agents do can be taken at face value. Deceit means nothing to them.

To be clear: The film does have a few flaws. Though it runs just over two hours, one wishes that it were slightly longer; the final scene with Bachmann feels abruptly truncated. We’ve grown to care about him, and we want to know how he emotionally and psychologically works through the final tumultuous developments in the central case. Also: Corbijn and co. do take one regretful misstep with their post-9/11 posturing. Annabel informs Issa about a Muslim terrorist attack that wiped out numerous civilians in a market, to which Issa responds, “Inch’allah” (or “God willing”). That line feels like a punch below the belt; outside of this scene, Issa is depicted as a quiet, gentle man with a traumatic past and a sincere faith in Islam. One might ask oneself what the filmmakers gain by indicating his support of jihad. This seems needlessly hostile and gratuitous, especially when the one other key Muslim character in the movie also has ties to jihadist activity. As it stands, the picture threatens to enter “not my daughter” territory with its uniform take on the Muslim world, and suffers for it. However, the film redeems itself somewhat with a damning (and politically correct) portrayal of twisted American operatives, notably Robin Wright as an ice-water-veined shrew.

All minor reservations aside, the movie must be counted as a great success. In terms of conception, performance, and execution, it is first-rate, and actually feels a bit superior to Tomas Alfredson’s 2011 Le Carré adaptation of Tinker. Though that was a very fine film in its own right, it occasionally felt top-heavy and laborious, as if Alfredson & co. were struggling to squeeze in too many elements of the novel. A Most Wanted Man is more efficient — sleeker on a narrative level, more intelligently gauged, slyer in its ability to slip up on us and catch us off guard. In hindsight, we realize that every scene, every line of dialogue, every action, has contributed a piece to a giant, gorgeous mosaic — and all lead up to one of the most shattering, emotionally devastating payoffs in recent movies.